How Do We Become Us?

In English, when you wish to refer to a group of people who originate from the same geographical location and share a common culture, you call them a nation or a people. In Torah vernacular, the children of Israel, the descendents of Yakkov/Jacob are referred to as an am, edah and goy. Traditionally am has been translated as people, edah customarily is rendered as congregation, and goy is commonly interpreted as nation.

It is axiomatic that the terms employed in Torah are precise. Yet, before we begin to explore the nature of these three terms we ought to ask ourselves, what is it that creates a nation? In a time of great nationalistic pride, where it seems that every ethnic group which converses in a distinct dialect aspire for their own homeland and sovereignty, we need to re-ask the question, how do we define a people? Common language is ruled out from the mere fact that there are many nations that share a language and yet are diametrically opposited in terms of government and culture.

But what is culture? Years back, in the West, culture meant what is called ‘high culture’- the fine arts, classical music, live theatre- but, for the most part, these forms of entertainment were shared by a very small group of people. True, there are those who argue that there is, for instance, an American ‘core culture,’ such as consuming great quantities of fast food, watching a lot of television and movies, and rooting for your local sports team. But suppose one does not enjoy fast food, barely watches TV and is not a sports fan, would this person be considered less of an American or unpatriotic?

Birth of a Nation

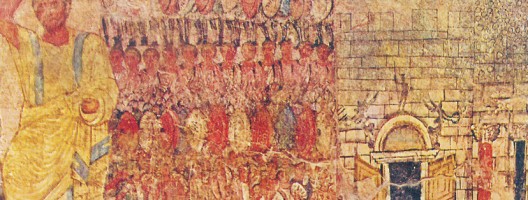

The going out of Egypt is viewed as the birth of the nation of Israel. The preceding enslavement was the labor pains, and the exodus, the birth. So let’s observe the language the Torah employs when discussing the nation’s birth and see if we can unearth a pattern that bespeaks national identity development and spiritual evolution.

Prior to the exodus, when Moshe/Moses is first being appointed as the redeemer, the Torah says; “And Hashem said; I have surely seen the affliction of my people who are in Egypt, and have heard their cry because of their taskmasters; for I know their sorrows.” (Exodus 3:7) The precise phrase the Torah uses is ami- my am- my people.

The narrative unfolds. The children of Israel, still in Egypt, receive the mitzvah of korban pesach – the divine invitation to offer a sacrificial lamb. The Torah says; “Speak to all the congregation of Israel, saying; In the tenth day of this month they shall take every man a lamb, according to the house of their fathers, a lamb for a house” (Exodus, 12:3). The phrase used here is adas, the plural of the word edah – as in congregation.

Following the exodus, as the people of Israel stand at the foot of Mount Sinai, the Torah speaks once more; “…if you will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then you shall be my own treasure among all peoples; for all the earth is mine; And you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests, and a holy goy (nation)” (Exodus, 19:5-6). The term used in this, the third statement, is goy-nation. This goy categorization is apparently the climax. Indeed, at the very beginning of their collective journey, when the forefather Abraham first encountered the Divine, he was told “and I will make you into a great goy-nation” (Genesis 12:2). The message of the objective was clearly defined, the metamorphoses of his descendents into a great ‘goy,’ which was eventually achieved when they stood at Sinai and were receiving the Torah.

So there are three evolving stages, The first stage is that of the children of Israel as referred to by ‘am‘—that is the pre-mitzvot, pre-Torah stage. The Jewish nation, as a people, are afflicted with suffering and in an ontological condition of deep exile. The second stage occurs when they are introduced to mitzvot, and are called ‘edah.’ And finally, as they are about to receive the Torah, they are identified as a goy.

Am is the weakest definition of a people. In fact, the word am means weak, as in gechalim omemus-barely lit coals. Then comes edah, from the root word ed-witness, and then the term goy as in g’viyah-one body.

Am-People

In a pre-mitzvot, pre-torah reality, in a situation where there were no—or little—distinct laws and rituals, what forged them together as a people was their common enemy. Being communally oppressed in Egypt, their external predicament pressed them together into a unified group. Indeed, there are nations and people that coalesce as one group solely because of outside oppression and persecution. This is an am, a nation of sort, but a shallow one indeed. Take away the outside influences and the internal structure of the nation crumbles.

Edah-Congregation of Witness

Beyond am is edah, it is where a group of people beyond geographical circumstances are unified by abiding laws and shared customs. An edah is an assemblage of people whose lives become a testimonial to a higher order, divine law or an overarching state law. With regard to the children of Israel, they become a witness to Torah. In the words of Rav Saddiah Gaon, the tenth century philosopher, “the nation is not a nation, only with Torah.” Upon receiving the mitzvah of karbon pesach, they can be called an edah.

Goy-Nation

Ultimately a true nation is a goy—as in one body. This occurs when a group of individuals who share a common law and aspire to a common goal evolve into, metaphorically speaking, one goy, one body. The group becomes so linked to each other that it is as if they exist within one body, albeit with different functions. If one limb is damaged, then the body as a whole aches. This transpired at the foot of the mountain where they camped, as the Midrash extrapolates from the verse, “ke’ish echad, be’lev echad”-as one person with one heart.

Yid-A Single Jew

Thus far we have explored what constitutes the nation. But what of a Jew as an individual? Suppose there is a Jew who does not, as of yet, espouse an outward willingness to be a living edah. The individual may not wish to be part of the goy, with that nation’s national and spiritual destiny and ambitions. While they may no longer identify themselves as part of the Nation, they are still Jewish in Torah Law, and for that matter, they are still considered a Jew to an anti-Semite. So what is it that makes an individual a Jew, even when the person himself no longer wishes to express any Jewishness?

Anti-Semitism

Some modern philosophers, such as the French existentialist Jean Paul Sartre, would like to suggest that the Jew is only the Jew because of the anti-Jew, the anti-Semite. To him, if there would no longer be the anti-Semite, there would no longer be the Jew. “What is it, then, that serves to keep a semblance of unity in the Jewish community…if they have a common bond, if all of them deserve the name of Jew, it is because they have in common the situation of a Jew, that is, they live in a community which takes them for Jews” (Anti-Semite and Jew. Chap 111). So the Jew, as an individual, and to Sartre, as a community, only exists because of externalities. But such reading is merely superficial, indeed one of Sartre’s weaker books, as it underscores the importance of the law, culture and custom, and certainly the divinity of Torah.

Culture Shock

Being that adherence to Torah and her values cannot be the sole root of Jewish identity since even those Jews who do not claim Torah as their own and as a way of life are still considered Jews, perhaps it is Jewish culture that creates the Jew. But what is Jewish culture? A lot of the Jewish culture that we know in the West is not Jewish culture per se, rather Ashkenazic/ European Jewish culture. Jews from Africa or the Middle East have an altogether different culture. They do not eat gefilta fish or chicken soup for Shabbas dinner, nor is their native language interlaced with Yiddish terminology, such as schlep, kvetch, or yiddisher kop.

One Family

Blaise Pascal, one of the greatest minds of the seventeenth century, the person who when asked by Louis XIV for proof of God’s controlling hand in the historical process, responded, “Why, the Jews, your Majesty, The Jews!” penned these words about the Jews: ” I see first of all that they are a people wholly composed of brothers…are entirely descended from one individual, and being thus all one flesh and members one of another comprise a powerful state of a single family: this is unique” (Pensees).

I believe that this description; viewing Jews as part of a family, descendents from one individual is right on the mark. Clearly, this is aligned with the definition of the Jews as “bnei yisrael-the children of Israel”, the offspring of the patriarch Yakkov/Jacob.

Within the nucleus of a family there are always different types of children; some of them are more obedient than others, some more involved in the path of their parents than the others, while some more rebellious. The diversity within the family unit is part and parcel of the family dynamic and what keeps it so interesting.

Conversion as a form of Spiritual Adoption

Clearly, this sense of family extends itself outward and embraces those Jews who choose Judaism, as they too become part of the family, so to speak, like marrying into the family. For this reason the initiation process for the one who wishes to join is a bit more difficult than for the one who is born into it, as the individual needs to prove himself, and accept upon himself or herself the Torah, the good that comes along with being in the family, as well as the harsh reality of persecution, prejudice and anti-Semitism. But once joined they become a part of the family as any other member—this is sufficient, without taking into consideration the more mystical interpretation that the convert is part of the family to begin with.

All members of the family are eternally part of the family, whether they are committed from birth, converted or cast-away. They may even outwardly lack a connection, but they are forever part of the Family, and always remain a Unique Jew.

Light unto the Nation(s)

As the physical mirrors the meta-physical, those who are part of one family are not merely genetically related but are spiritually connected, and the physical relationship is but a manifestation. Tellingly, every group of people, every nation shares a common overarching ‘soul’ which is reflected in the group’s collective ambition, goal, and trajectory. This spiritual commonality shows up in the uniqueness of the music these people enjoy, the food they traditionally eat, and the general life style of the group.

In an interview, the Noble Laureate Joseph Brodsky was asked about his connection with Judaism and he replied “there are a number of elements in my life that define me as a Jew. The passion for justice, and my love for the intellect.” These words echo the words of the great Albert Einstein, who is quoted in Ideas and Opinions, as saying, “The pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, an almost fanatical love of justice, and the desire for personal independence—these are the features of the Jewish tradition which make me thank my stars that I belong to it.”

Ever since the patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and the matriarchs, Sara, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah challenged their polytheistic surroundings and, with self-abnegation, relentlessly sought justice, taught and inspired monotheism, and thus accountability and responsibility, transforming their mortal reality and themselves into paragons and archetypical figures. This has been encrusted into the fibers of their ‘family,’ penetrating the most profound levels of our consciousness, namely, a deep level of faith- both an innate faith in the Creator and faith in the abilities of mankind to spiritually evolve and pursue justice. In fact, it was the Jew who gave the world these very ideas of faith, progress and justice. To quote Thomas Cahill’s best selling book, “Most of our best words,—new, adventure, surprise, unique, individual, person, vocation, time, history, future, freedom, progress, spirit, faith hope, justice—are the gifts of the Jews.”

The collective goal and ambition of the Jew is to bring redemption to this world, to bring peace, light and harmony to a world of seeming chaos, darkness and confusion. Every letter in the Hebrew alphabet has a number equivalent. The word yisrael, comprised of five letters. The same as the Hebrew word for light- “or”- aleph/1, vav/6, reish/200, and darkness, “v’chosech,” vav/6, ches/ 8, shin/ 300, chaf/20, grand total 541. Indeed our national goal is to inspire a fusion between light and darkness. As a family, we continue to be a light unto the nations. Bringing light where there is darkness, warmth where there is cold, and a ray of hope when despair threatens to overwhelm.