Only free people have names. A slave is a nameless statistic, with no independent personal identity or existence. Likewise, when we are slaves to our emotions and reactions, we have no independence from the stimuli or influences in our lives.

Read more...When we call something by a name, we define it and create a relationship with that thing. Once we define the subject or object, we can interact appropriately.

Read more...to purchase this book

click here to purchase this book

Below is an excerpt of ‘Exploring the Tradition of the Upsherin’

[issuu layout=http%3A%2F%2Fskin.issuu.com%2Fv%2Flight%2Flayout.xml showflipbtn=true documentid=100430010041-bf155922c3ed466cba04c5eb33c6aae2 docname=upshernish_nocover username=shiryaakov loadinginfotext=Exploring%20the%20Tradition%20of%20the%20Upsherin width=600 height=464 unit=px]

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Upsherin

Chapter 2: The Idea of Orlah – Blocked Energy

Chapter 3: The Age of Three: A Time of Transition

Chapter 4: Three Stages of Child Development

Chapter 5: Boundless & Borders: Circles & Lines

Chapter 6: Uncut Hair vs. No Hair & the Balance in Between

Chapter 7: Three Forms of Head Hair: Detached – Masculine – Feminine; Exploring the Meta-Nature of Men & Women’s Head Hair

Chapter 8: Male Hair & the Act of Transforming Judgment into Compassion

Chapter 9: Basic Customs of the Upsherin

Chapter 10: Afterword

The Story of Purim with Commentary, Interpretations and Kabbalistic Insight by Rabbi Dovber Pinson.

Pay and download PDF?

Kindle/eReader version?

Kabbalah holds the secrets to a path of conscious awareness. This compact book presents 32 key concepts of Kabbalah and shows their value in opening the gates of perception.

Read more...The study of music as response is explored in this highly engaging book. Music and its effects in every aspect of our lives are looked at in the perspective of mystical Judaism and the Kabbalah. The topics range from Deveikut/Oneness, creating soulular fusion, to Yichudim/Unifications, merging heaven and earth, to the more personal issues, such as Simcha/Happiness, expressing joy, to the means of utilizing music to medicate the sad soul. Ultimately, using music to inspire genuine transformation.

To purchase the book:

This book is available in all fine book stores and on the web at Amazon.com and Barnes and Noble.com.

http://www.amazon.com/Inner-Rhythms-Kabbalah-DovBer-Pinson/dp/0765760983/ref=pd_sim_b_4

We live in an age of great confusion and uncertainty. There is a devastating lack of leadership; both on a collective/global and individual/personal level. Clearly, our life, and life in general, seems to be spinning out of control.

Read more...Kedusha, holiness–and every truly positive phenomenon in the world–is eternal. A Yom Tov- a religious holiday is not merely a remembrance of a past miracle or positive event. It is a celebration of the reshimu, the eternal imprint of the transcendental event, which is revealed anew on its original date, every year. The very same force that brought the original miracle into the world is vividly present on its respective holiday. Like lovers who celebrate the anniversaries of all their tender exchanges, several times a year we spend time with the Divine Presence, delightfully re-living our most romantic moments.

The nature of everything unholy or negative, on the other hand, is to fade and disappear. And yet, on the day of Tisha b’Av, we fast, afflict ourselves, and mourn events that happened thousands of years ago. On this day, the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem were tragically destroyed, and the Jews went into exile. On this day, circumstances physically forced the lovers apart.

Wounds, however, heal. Yes, it is true that throughout the centuries our wounds have been reawakened on the very day of the Ninth of Av–for example, with the Expulsion from Spain in 1492. Yes, in that sense, the Ninth of Av is a ‘bad day’. Nonetheless, so many centuries after the destruction of the Temple, there really should be no negative reshimu lingering on this day. Negativity does not have such staying power. What, then, is the connection between our fasting and the destruction of the Temple?

REDEEMING FACTOR

Human beings tend to turn outwards in times of joy, and turn inwards in times of tragedy. Negativity seems to break down our egoic resistance to the experience of the Transcendent. Tragedy and anguish, even more than joy, tend to bring people into spiritual introspection and self-evaluation.

Without denying the great tragedies of Tisha b’Av, there was a redeeming factor: the people who lived through these events were shaken out of their spiritual complacency. They were shaken to their core, and powerfully motivated to make teshuvah–to return to the depths of their true selves. This is the positive, holy imprint of those events, and this is why Tisha b’Av is considered a holiday.

Unlike other holidays, of course, this one is ‘celebrated’ by fasting and mourning. In order to tap into the day’s positive imprint–in order to shake ourselves out of our own complacency–we must tap into our brokenness. Activities such as fasting and reciting lamentations sensitize us not only to the tragedy of the historical exiles, but to our own exile, our own separation from who we really are. We too can allow Tisha b’Av to motivate us to make teshuvah.

FROM DARKNESS, LIGHT

In order to construct something new, the old must be deconstructed. In his book, Netzach Yisrael, the Maharal, (Rabbi Yehudah Loew, 1525-1609), explains that the destruction of the Temple was the extinguishing of an old light, so that the new, greater light of Moshiach could be revealed. The Midrash says that Moshiach was, or ‘is’, born on Tisha b’Av. Such profound light can only be revealed within darkness.

DIVINE EMBRACE

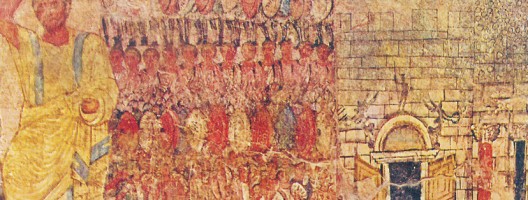

The Talmud says that when Israel was not aligned with the Beloved Creator, the two golden Keruvim, or Cherubim, that adorned the Ark of the Covenant, miraculously turned and faced away from each other. When Israel was aligned, the Keruvim turned to face each other. On Tisha b’Av, as we were being expelled from the place where human and Divine kissed, it would seem that the Keruvim should be facing away. However, as the Romans were ransacking the Temple, they entered the Holy of Holies. There, they found the Keruvim enwrapped in an intimate embrace.

Lovers make their most dramatic demonstrations of love when they must leave each other. At the moment that we were being torn away, a sign of indestructible love manifested. In the anguish and passion of this embrace, our Redemption was conceived.

When physical closeness is impossible, the longing of lovers to connect is intensified. Over time, constant yearning can deepen into a spiritual maturity. It is precisely within the atmosphere of exile that Redemption gestates, matures, and is finally born.

KINDNESS IN SEVERITY

The first nine days of the month of Av consist of 216 hours (9 x 24 hrs). 216 is the gematria, the numerical value, of the word gevurah, ‘severity’. It is also the gematria of word aryeh, ‘lion’, and the astrological sign of Av is Leo, the lion. One of the epithets of the Holy Temple is Aryeh, referring to the leonine fire that consumed the sacred offerings. All this suggests that during the Nine Days leading up to Tisha b’Av, great severity manifests in relation to the Temple.

Looking deeper, however, 216 is three times the numerical value of the word chesed, or Divine kindness (72). This tells us there is deep chesed in gevurah, and gevurah in deep chesed. The passionate lovers of Hashem consider it a great ‘kindness’ when they are reminded of their Beloved–even when, in their anguished yearning, it’s impossible eat or drink.

May we merit to see our longing fulfilled!

The going out of Egypt is viewed as the birth of the nation of Israel. The preceding enslavement was the labor pains, and the exodus, the birth. So let's observe the language the Torah employs when discussing the nation's birth and see if we can unearth a pattern that bespeaks national identity development and spiritual evolution.

Read more...When we recite the Hagadah, we should take it personally--it should liberate us. Therefore, all of the characters depicted in it should be seen as reflections or representations of different parts of ourselves. We need all three elements, Moshe, Aharon, and Miriam, in order to bring about a redemption from our 'stuckness'.

Read more...Olam — the Hebrew term for world, universe, creation — is rooted in the word helem (concealment). The way this material-based universe operates, the way it was set up and created is that creation does not unambiguously point to a creator, notwithstanding the classic philosophical argument made famous in medieval Europe, of design; as a painting is proof of an artist, or a book of an author. Despite this logical reasoning, there are those who look at creation and see nothing. Some claim to see, instead of the presence of an intelligent Source, a great void or emptiness. Just because the odds are extraordinarily slim that this universe could be a random occurrence does not, to some, render this impossible. They seem to suggest that this profoundly intricate world is one fluke in an infinite meaningless chaos.

“If God exists,” one witty modern philosopher once wrote, “then He has written a detective story with all the clues pointing the wrong way.” Certainly, for some believers, proof of the creator is found scattered throughout all of creation, from a sunset to the birth of a child. But others simply don’t find such evidential proof — for some these are mere natural occurrences. Indeed, on some level they are the working of nature. This, however, is where the concept of miracles comes into play.

While nature conceals, miracles reveal. Nature may not point overtly to a creator, but miracles do. In the world of miracles there are two types: miracles that shatter the workings of nature, suspending and overwhelming the natural course; and miracles that are vested within the workings of nature, miracles that intermingle with what we call nature.

There is Teva (nature), and there is nisim geluim (open miracles) and nisim nistarim (hidden miracles). Open miracles defy logic. When they occur, our conventional mood of thinking is suspend, and we stand in awe at the occurrence. There is no way for us to honestly grasp what just occurred, and the least we can concede is that we don’t yet have an explanation. Concealed miracles pique our interest and rouse us to take a deeper look, but they do not force us to submit our lack of understanding. When a hidden miracle transpires, the hand of God can be detected to those who wish to see it, but only indirectly. Evaluating the details of the event, we come to a realization that something mysterious was and is at work.

Purim is the embodiment of a miracle wrapped within the costume of teva/nature. Taking a superficial glance at the story of Purim, nothing miraculous pops up. The story seems to be obscured in ambiguity and chance occurrences. Just a simple reading of the text offers a tale of chance and coincidence, nothing miraculous or out of the ordinary. And yet the details don’t add up unless we attribute the mysterious unfolding to a higher power and cause. True, no one event is miraculous or out of the ordinary; still together there is an incredible combination of circumstances and events that weave a fantastic tale of the remarkable.

Let us revisit the story once again: The story opens with Achashverosh throwing a great feast and wanting to show off his queen Vashti. He asks her to appear but she refuses. Angered at her refusal, the king gets rid of her and searches for a new queen. So far nothing miraculous has yet occurred. It so happens that the girl the king saw fit for his new queen was none other than the Jewess Ester, the cousin of the court Jew Mordechai. Some time later, by mere ‘coincidence,’ Mordecai overhears a plot to kill the king and informs the court and saves the life of the king. Meanwhile Haman, the wicked adviser of the king has plotted to kill off the Jews in the kingdom with the consent of the king. One sleepless night as the king is tossing and turning in bed, he asks to be read from his book of remembrances, and the tale of Mordechai saving his life is retold. A bit later on, Ester reveals herself as a Jew and asks for the decree to be annulled, and to top it all off, when the king walks into the queen’s chamber, he finds Haman there, and his anger is sealed and the decree revoked.

Essentially this is a tale of great happenstances or coincidences. As a whole, there are no events or one event that stands out as miraculous. If anything, the miracle is a hidden one, weaved within the fabric of the story. Unlike Chanukah, for example, where a jug of oil with barely enough oil to last one day burned for eight days, or Passover, where a group of slaves were saved and redeemed, the story of Purim does not manifest any such events. It is a tale, a miracle that is hidden, enclothed within the workings of nature. So much so that it even lends itself to be ascribed to mere happenstance or coincidence.

Ester, the one who appears to be the heroin of the tale, is obscured in a great hiddenness. No one in the court knows her identity. Remember she does not even tell her husband, the king, her point of origin. Furthermore, her Hebrew name is Hadassah but she takes on a new Persian name Ester, which means a star. So much so is her life a secret that even her new name hints to secrecy as well. Ironically, the name Ester in Hebrew is derived from the root word “str” — hidden As the Talmud equates her name with the passage in the Torah, God says: “I will surely hide (hastir astir) My face from you…” (Deut. 31:18) There is a double measure of hiding, hastir astir — the depths of hiding. She is living with her identity in secret. She hides in her new identity and name, Ester, and the name she assumes means also hiding.

There are many levels of hiding. Basically one is a hiding that screams to be found while that other is such a deep level of hiding that no one looks any longer, and the fact that something is hidden is itself hidden.

This is reminiscent of the story of Avraham, the son of the Maggid of Mezritch. Once young Avraham burst into his father’s study and began to weep bitterly. He had been playing hide and seek, he told his father, and having hidden in the ultimate hiding place, he waited, and waited, to be found. When after a long time he emerged from his hiding place, he found that his friends had given up on finding him, forgot about him and had gone on to other games. He hid so well that the fact that he was hiding was hidden. After some thought, the Maggid tearfully said; “Our creator plays a game of hide and seek with us. The objective is for us to find, discover and reveal heaven within a grain of sand. For some the cover up, the concealment is so thorough that soon they forget that there is a game being played. How sad it must be for the One who hides.”

The story of Purim speaks of such depths of hiding. The other great heroin of course would be God, certainly as the scroll is one of the books in the Torah. Yet this book is unusual in that it does not contain any of the traditional biblical names of God. Mordecai seems to make a vague reference to God when he says to Ester that the Jews will be saved if not by you, then by someone else. But the typical names of God are not present. Some early commentaries point out that the reason there is no mention of God is because since the story of Purim was also recorded in the native language of Persian for the archives of the kings, had the name of God been explicitly written, idol worshipers of that generation or of years to come would read the names of God as idols. To assure that a book of Torah does not become a source of idol worship, the holy name of God was omitted.

Notwithstanding this interpretation, there is a deeper reason for the overt omission. Everything can and should be understood on multiple levels. The fact that this book does not mention God is more than to simply negate a negative result, but there is a positive understanding of this, as well, as we will shortly explore. Everything is divinely orchestrated, and the fact that the name of God does not appear indicates the idea of concealment. So much so that there are those who can read the tale of the Megilah as another great story in the history of world literature.

The name the holiday is representative of this idea of hiding. The name that we call the holiday also reflects this apparent randomness of nature and coincidence of occurrences. Purim is called Purim because Haman cast a Pur — a lot to determine the day he desired to rid the kingdom of the Jews, and so the day is called Purim. We don’t choose the outcome of a lot; it chooses for us. We have no control over a lottery, wish as we may. It appears to be something of random, without choice and purely accidental.

Today as we celebrate this holiday, we drink and imbibe intoxicating sustenance more than the usual. Some of us wear masks and dress up; all this reinforces the concept of causation and hidingness. Purim is divinely arranged to be in the month of Adar which possesses the astrological sign of Pisces. Fish are surrounded and encircled by water. They are engulfed by water, their source of nourishment; otherwise they cannot survive. Water covers them; fish exemplify the idea of hiding.

Still and all — and this is why this day is a holiday, a festive and cheerful time — the point of it all is to reveal the hidden, to show that there is really no such thing of happenstance or mere coincidence. As Ester means hidden, the word Megilah means to reveal, as in Megale. The scroll of Ester, the Megilah of Esther literally translates as “revealing the hidden.” The objective thus becomes to read the scroll, to read into the story and uncover within the story, within the maze of the seemingly unrelated and chance events, the hand of God. By deeper reading and paying attention to tale as its being unfolded, one comes to this amazing realization; the awareness that nothing simply occurs.

On a cosmic level the female heroin of the story Ester is the embodiment of the entire Keneses Yisrael — the congregation of Israel. The creator’s relationship with creation is viewed often in terms of man and wife, or male and female. The male impregnates and offers, while the receiver, the female is where creation is birthed and actualized. The bounty and spiritual plenty comes from above but ultimately is revealed, though often with the hardships of labor, through the articulation of the below.

Nature on its own conceals the divine energy that sustains it. Elokim is the source of nature, as both Ha’Teva — the nature and the divine name Elokim have the numeric value of eighty-six. Speaking of creation, the Torah says “in the beginning, Elokim created.” Elokim, the aspect of concealment creates a universe of concealment. Philologically speaking the name Elokim can be spilt into two words, Elam — muted and Yud/Hei – a name of God. Together it means that Elokim is the limiting force that mutes the more transcended energy of the Infinite. Still, the divine light is there, just there silently. Our task becomes to discover, unveil and reveal God within nature, to put together the puzzle and see the hand of God within the workings of nature. Purim is a holiday which allows us and gives us the strength and vision to observe this truth. Ultimately it empowers us to elevate the seemingly ordinary present into something extraordinary; transforming the natural into the miraculous and the everyday into the unique.

Lights seem to speak to us in a very deep way, particularly those gentle lights that dance atop of candles. There are few visuals that are as warming to us as the sight of a burning flame, a pure simple flame luminous and ethereal.

To the mind lights and festivities also seem to go together; lights are deemed the perfect vehicle to express joy, a firework display at a festive occasion is but one example, as is the lighting of candles or the hanging of colorful bulbs at a party or any other joyful event.

Within a Jewish context every Shabbat, holiday or other special occasion demands the lighting of the candles. As the day is about to begin, at the moments immediately proceeding the beginning of the auspicious and dedicated day the tradition is to light a candle. More precisely, the Shabbat candles are lit for the purpose of Kavod – honor, to pay tribute to the day, and also for the purpose of Oneg – pleasure, so that we eat our Shabbat meal in the pleasing glow of light, and do not stumble in the darkness. On Yom Tov we have the additional advantage of it being a day of Simcha, a day of joy.

The oddity of all of this is that the candles of Chanukah are not meant to be used for our personal pleasure whatsoever, it’s quite clearly stated that one may only gaze at the lights and not use them for any other purpose. In fact, another light or candle must be lit to ensure that the room is lit even without the light of the Menorah.

The intensity of these lights are not meant to be a channel for something else, no matter how lofty that purpose may be, they are not intended as a means, but are there as an end unto themselves.

“The soul of man is a lamp of G-d” (Proverbs 20:27.) The soul is our higher self. Our soul is the self of our potential and possibility, the part of us that stands above ego, selfishness, aggression and resentment. The soul is the background of our being, the light that masters our thoughts, emotions and actions, and essentially the whole of life. It is not something we posses, rather it is who we are, it does not belong to us, it is us.

And yet we have the ability to eclipse the light of our soul, and use its reverberating power to destroy and wreck havoc. Light can be warming and bring comfort, but it can also be the source of much destruction and devastation. We can harness our internal light to bring love and joy but the converse is also true.

Cumulatively, to sum total of the lights we kindle throughout the days of Chanukah is thirty six, as in 1+2+3+4+5+6+7+8=36.

Thirty six, the mystical and mysterious number is the amount of times the word Or- light appears in throughout the Torah. (Rokeach) Thus, in every generation there are thirty six hidden Tzadikim – elevated souls present who sustain, nurture and guard the light. Concealed, unassuming, and virtually unknown, these thirty six righteous people are completely attuned to their inner light and the inner lights of creation.

After the incident in the Garden of Eden God asks Adam ” ayeka — where are you”? (Genesis) Not merely to be polite, and show the way we should enter a conversation, (Rashi) but the question is essentially “where are you”? What have you done with your life and light? It is a question that is asked and re-asked throughout time of every one of us. The inner voice within challenging us once in a while and questioning, “Where are you”? What are your priorities? And what do you want out of life? Are you living up to your potential?

Midrashic sources write that the numeric value of the word ayeka is thirty-six. (Midrash Zuta, Eichah 1:1) The question is then more pointedly, “where are you”? “What have you done with your light”? The Hebrew word sapir, as in the English derived term sapphire refers to light, a stone of light. The word sipur — story is rooted in the word sapir. And so the question of ayeka is a question of, what is your story? What kind of tale are you weaving? Are you bringing warmth and joy, are you illuminating and bringing light, or have you forgotten your essentiality and are writing a story not worth repeating? This echoing sound of ayeka is a question, but more importantly a prodding, to be more, to live up to our potential.

Ayeka, as in “what are you up to? How have you cultivated revealing your inner light?” Is the essential question to which your life should be the response. This question begs a response every day of the year, but comes into greater focus on the 25th of Kislev, the beginning of Chanukah, when we begin kindling the Chanukah. Appropriately the 25th word in the Torah is Or -light.

These are the lights, our lights, that gently whisper to us to turn aside, refocus, and reengage our attention from the overwhelming bombardment of the everything and take notice of what is right here, who we are, and what we can be, allowing us to glimpse inwards to a place deep within us, and rediscover that which has always been there.

Over the years, a custom has developed that on Rosh Hashanah, during the course of the day, we go out to a living body of water with lively fish swimming therein and symbolically cast away our unwanted negative baggage. We take hold of our negativities, the devastating weight that presses us downward, and throw them into the waters. The act causes us to reflect inwardly, as we aspire to unburden ourselves of the negative elements within us and toss them into the waters to be covered over and washed away.

Rash Hashanah is a time of renewal, and in the new reality we are creating for ourselves, we wish to put aside the old self, perhaps forget about it and even throw it away. We reason that a radical shift in being is required. Most often, for something to change from what it is to what it desires to become there needs to be a moment when it ceases being what it is. A seed rots in the earth before it can offer new life; first comes sterility, then fertility. So we look at ourselves and look at the old image of the negative self and we let it go, let it slide into the waters.

A mere few days later, the festival of Sukkas comes around. In Temple times during the holiday of Sukkas, a festive celebration with ecstatic dancing and lively music took place as folks went to fetch water from the well to lubricate the Altar the following day. Though in the Torah there is a clear source, the sages intoned the verse that explicitly states, “You shall draw water with joy from the wells of salvation.”

This celebration was called “simchas beis hashueva- the joy of the drawing of the waters.” The joy was so immense and overwhelming that the sages of that time declared; “He who did not see the joy of simchas beis hashueva did not see joy in his life.” It was impossible for someone who has never experienced this celebration to truly appreciate what joy is all about. But why the joy? After all, it seems like a pretty simple, almost mundane act of drawing water.

The Rambam, Maimonides, seems to suggest that since with regard to the entire holiday of Sukkas the Torah says, “And you should be happy before Hashem your God for seven days” (Vayikra 23:40), and the soubriquet of Sukkas is “zeman simchaseinu – a time of our joy,” therefore, as a result of the overarching theme of joy during Sukkas, the joyfulness overflowed and inspired dancing and music during the fetching of the water.

Yet most commentators assume that there is an intrinsic relationship between gathering the waters and the ecstatic elation that was experienced and expressed.

While joy and happiness is our natural state, our ontological conditioning, often we lose touch with ourselves and we find ourselves down, dispirited and sad. To reclaim our birthright and to reattain our joy we need a stimulant. Often what evokes our joy is precisely the regaining of something that was lost. We all know the joy we sense when we are reunited with an old friend, when a person we love returns from a long trip, when spouses resolve a conflict, or for that matter when you lose your keys and then, after frantically searching, you find them. The joy comes from righting what is wrong, the sense of repairing the broken and making complete and whole that which has been shattered and fragmented. This is all part of the cosmic melding, the ‘two’ back into the ‘one.’

If in the initial stages of growth a radical brake is required, eventually a more drastic ingathering must take place. While during Rash Hashanah we cast aside the hindering elements of self in the waters, and that was beneficial and productive at that fragile stage, now we need a full embracing canopy, a Sukkah which will include all aspects of self. Now that a healthier self has emerged, there needs to be a reintegration of all aspects of who we are on this higher and deeper level. The joy is the reunification with our very own selves.

But how do we reintegrate and collect the old and broken parts of self? And what affords us the ability to do so?

A tear is a cleansing agent. The waters of our tears rinse out, purify and ultimately allows for full transformation to transpire. In between the two extremes of throwing into the water and gathering from the water are “the ten days of teshuvah.” In these honest days of introspection and deeply opening up, who is not moved to tears?

If you are aware and conscious of the times, and you open up and expose all of yourself to yourself and let it all come out, you will eventually find yourself crying. If not, says Ari R. Yitzchak Luria, “your soul is not complete.” Something is seriously amiss and drastically disaligned. Paradoxically, this awareness itself of your lack of inspiration will catapult you and may even shake you out of your complacency and spiritual insensitivity. Either way, by the time we have reached the climax at the end of Yom Kippur, our tears have utterly inspired a total reorientation so that we can recollect and re-gather our lost parts and establish them within the new elevated context of our life.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of tears. There are the bitter tears of sadness, of loss and of yearning, but there are also the tears of joy and of reunification. Abraham cries when Sara dies, but Jacob also cries when he first encounters his future wife Rachel.

During the days of teshuvah, culminating with Yom Kippur, the tears that flow are most often bitter tears of yearning, desiring to reunite, return and come closer. Once Sukkas comes about, the tears that may flow are tears of joy, of oneness and a healthy sense of reunification and belonging. Sitting in the Sukkah, we are present within the makifim of binah – the surrounding energies of divine comprehension. The walls are the makifim – surroundings, and sitting down, settling down, translates the bringing down of the transcendent within the immediate.

As we are sitting within the makifim of binah we are resting within the warming and gentle embrace of eima ila’ah – ‘supernal mother.’ Being engulfed within this sacred and protected space, we may feel overwhelmed to the point of tears, but here the tears are tears of joy, of a child returning and running back into the arms of his mother. After the arduous journey through Rash Hashanah and Yom Kippur we are finally home. We have arrived, and arrived with the totality of who we are.

| As the night of Rosh Hashanah—the cosmic story of creation—is unfolding, lets begin our own journey with a story.

The Rebbe of Lelov awoke with the dawn, washed, and rushed to the synagogue for his morning meditations and prayers. While hurrying along the path, the Rebbe chanced upon a student. Surprised to see another awake at this hour, the Rebbe inquired as to his intentions. The student duly reported that he was on his way to the village bakery, where he was employed. He bowed his head in shame. “Master, it is shameful, you arise with the dawn for such noble a purpose, and I awake merely to bake bread.” The Rebbe gently corrected the young man. “In each of us lies the innate desire and power to create. This manifests itself as a yearning to create and share our creations with others. In each of us this manifestation is unique. My contribution is that of teaching and inspiring, and you, you give the village the gift of bread…” We all strive to be creative and creators. Sefer Yetzira-the book of formation is perhaps one of the oldest Kabbalistic texts around. It speaks of the mysteries and deepest secrets of creation, and it speaks of the Creator as the scribe and creation as the story. Philosophers and mystics have attempted to decode its secrets for centuries. Traditionally, this sacred text had been read as a narrative describing the Creator’s process of creating; yet others have opted to view the text as a manual for our own role in creating our reality. The process of creation is continuous, both on a cosmic and personal level. Largely, we observe on the outside what exists on the inside. What we see in the universe is a projection of internal universe, and this interpretation and reinterpretation is constant. Otherwise, how can we be responsible? How can we accept responsibility if we don’t acknowledge creatorship? Internally speaking, a creator is one who masters life and not the converse. A creator’s emotions and character are based not on coincidental circumstances that occurred to him, causing him to be a certain way; rather, those emotions come from deep within him (or her). The creator is the architect of his/her own existential reality, and not at the mercy of “surroundings.” There are those who must endure tragedy to gain empathy and those who must be surrounded by kindness in order to be open, loving and giving. The creator, however, does not allow himself to become what his external surroundings and experiences dictate; rather, he searches deep within his own mind and heart and develops empathy and kindness and all other emotions through true introspection and inner searching. He creates his own life experiences. This is on a personal level, building one’s character from within, rather than based on one’s surroundings. The Founder of Chassidic philosophy, the Baal Shem Tov, explained the words of the Torah in Genesis, “Let us create man” to mean, I’m giving you, the Creator says, your potential, now you create yourself together with me, develop yourself using your inner strength and abilities. There is the outer and inner world—one is the realm of the effect while the other is the cause. The internal inner world is the essential and the cause of the outer. When we surrender to the outer, then life is merely the effect. We will then continually find ourselves in situations and predicaments where we feel we have no choice whether to be there or not. However, if we live from the inside out, we then become and live as masters. And so, a beneficial practice would be to set the tone of the day during the first waking moments. The first thoughts, and especially the first words uttered, are very important in how the day will move along. If in the morning the first thing we do is become inner directed, that is we pray, reflect, become introspective, then the rest of the day will follow that course, and we will be the masters and creator of the day. We will be the cause of life and not the effect. However, if we choose to fill our mind in the waking hours with ideas that exist in the realm of the effect, then the day will follow that course, and we will find ourselves in the receiving end of life, finding ourselves in the effect, in circumstances and situations that seem beyond our control. |

Every time we promise and say we will or will not do this or that, we create a form of reality through our words. Therefore when our actions do not match that reality, an emptiness results. Vows uttered but not fulfilled are empty, lacking vessels of fulfillment. And in order to repair this lack—in order to build the necessary vessels— we need to remedy how we speak. We begin by becoming conscious of our words.

Read more...